What’s ‘Really Scary’ About Shein’s Breakneck Growth

“Really disappointing and actually extremely frustrating and quite scary.”

That’s how Rachel Kitchin, senior corporate climate campaigner at Stand.earth, described the results of the environmental nonprofit’s Clean Energy Close-Up, an update of the Fossil-Free Fashion Scorecard that it published last March.

More from Sourcing Journal

SNL's 'Xiemu' Ad Highlights the Appeal, and Ills, of Fast Fashion

Shein Will Work On Its Site After Scolding from German Consumer Org

Fashion's Current 'Pace of Change' Cannot Meet Collective Climate Goals

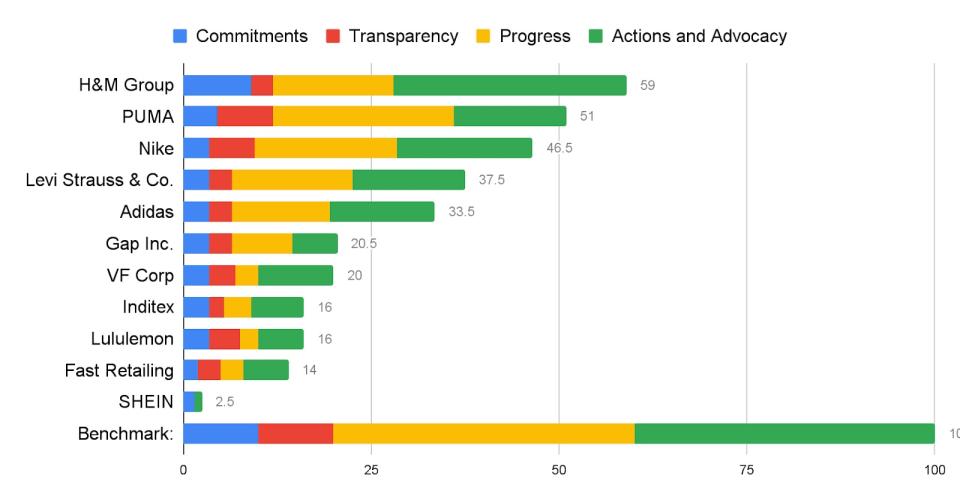

In fact, only three of the 11 household names it zeroed in on—Levi Strauss & Co., Puma and H&M Group—are “on track” to reduce manufacturing emissions by at least 55 percent by 2030 compared to a 2018 baseline, the new report found. The majority scored less than 25 out of a possible 100 points, with the worst-performing—that would be Shein—earning just 2.5.

But even the top flyer, H&M, barely mustered a passing grade with 59 out of 100 possible points, followed by Puma with 51 and Nike with 46.5. And for every hit, there was also a miss. Puma, for example, may draw more than 27 percent of its electricity use from renewables across two main supplier tiers, but most of it comes from “unreliable” renewable energy certificates, Kitchin said. Similarly, while H&M may be the only brand to offer grants to suppliers that install rooftop solar, it has yet to fully disclose how quickly it’s phasing out fossil fuels.

In short, brands continue to show a “real lack of urgency” at best, Kitchin said. At worst, they’re turning to so-called “false” solutions that could be tantamount to greenwashing.

“Kicking out fossil fuels from thermal energy and electricity is the No. 1 thing they can do to reduce emissions,” she said.

Puma has admitted to challenges. There is a need to rally the industry to wield policy advocacy to develop direct power purchase agreements as a long-term solution for shifting to renewable energy in its key sourcing countries, a spokesperson said. H&M also allowed that there is a “lot of work to be done on the path toward a more sustainable fashion future” and that it remains committed to “deliver on our ambitious climate agenda.”

It was Shein’s failing grade, however, that Stand.earth found among the “most concerning” of its findings. With Shein increasing its absolute emissions by nearly 50 percent in a single year, it now generates more pollution than the country of Paraguay, the nonprofit said.

“The emissions growth from Shein alone almost completely wipes out the emissions reductions that we’re seeing in other brands in the scorecard,” Kitchin said. “That in itself is hugely alarming. The scale of growth from that company is incredible. And then contrast that with the complete lack of action and lack of transparency from the company when it comes to what they are actually going to do to reduce that impact, it’s really scary.”

A Shein spokesperson said that the company is working to “mitigate climate change both within our operations and in collaboration with our suppliers,” including installing rooftop solar across Shein warehouses and supplier sites, implementing Clean by Design energy efficiency programs with more than two dozen suppliers and partnering with green logistics partners.

One barrier to change that experts broadly agree on is the fact that few brands run their own factories. As a result, there is a tendency for manufacturers to shoulder the yoke of the financial and operational responsibility for making improvements or complying with legislation. Where supply chains overlap isn’t immediately evident, which is why Stand.earth also published a Fashion Supply Chain Map, an interactive tool to identify opportunities for collaboration.

“I hope that brands will be able to use it to see the potential points of crossover,” Kitchin said. “And I also hope that people will get some understanding as well of how far there is left to go. Because I think it’s very easy for brands to present a shiny and happy image of all the work that they’re doing. But how that actually translates onto the ground is a really important piece, which is often missing. And ultimately, it’s these suppliers, the manufacturers themselves that have to do all of the hard work.”

Kitchin said that what the numbers tell us is that some of the world’s richest fashion brands are failing—failing people, failing the planet and failing workers in their supply chain. With the Canadian Competition Bureau’s recent announcement that it has opened an inquiry into Lululemon (16 points) following a “greenwashing” complaint from Stand.earth, brands should brace themselves for additional scrutiny, she said.

Most of all, as others have warned, the speed of progress needs to pick up, Kitchin said. 2030 is no longer some distant deadline, but a mere five-and-a-half years away.

“The good news is that the solutions are known. The solutions are there. And some of these brands are starting to enact them, but [they’re] in danger of being undermined by bad actors by greenwashing by a desire to maximize profit solutions,” Kitchin said. “Every year that passes we should be seeing real action we should be seeing significantly more transparency into what is really happening on the ground. And although the wheels are turning, it’s all happening too slowly.”

Yahoo Finanzas

Yahoo Finanzas